Empathy Swarm is now part of the ZKM Karlsruhe permanent collection.

Can breeding robots solve an empathy deficit?

Text by Matteo Marangoni

© Project and images Katrin Hochschuh & Adam Donovan

A jar of sourdough starter has exploded in my backpack. It was half empty just a few hours ago. Unbeknownst to me when I packed it, the creatures in the jar were alive and eager to expand beyond the capacity of the glass container. A sticky mix of flower and water is all over my copy of Valentino Braitenberg’s “Vehicles, Experiments in Synthetic Psychology”, a fun little book published in 1984 that describes a series of insect like machines expressing the emotions of fear, aggression and love.

In a farming area outside Hamm I received the incriminated jar from Katrin. Her and Adam are breeding a new species of robotic beings that are crawling around the floor of what used to be a living room. When she is not developing code for the robots, Katrin bakes an excellent loaf of bread in the adjacent kitchen. I want to learn how to bake like that too. Now the stuff is all over the pages of my reference literature.

Outside over the fields of wheat and corn a nuclear power plant impinges on the horizon. The plant used to house an experimental thorium reactor ominously named THTR-300. Nuclear chain reactions once contained in its core were brought to a halt following a leak of ionized particles into the environment that occurred at the same time as the disaster in Chernobyl in 1986. I think about other containers overwhelmed by exponential growth. I think of Al Barlett at University of Colorado at Boulder giving his lecture on arithmetic, population and energy over 1700 times. “Imagine bacteria growing slowly in a bottle. They double in number every minute. At 11:00 am there is one bacterium in the bottle. At 12:00 the bottle is full. At what time was the bottle half full? Would you believe it, at 11:59, because they double in number every minute. If you were a bacterium in the bottle, at what time would you first realize that you are running out of space? Think about it, this kind of steady growth is the centerpiece of the entire global economy.”

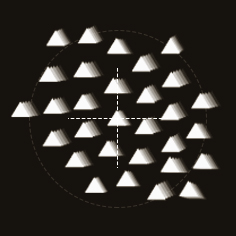

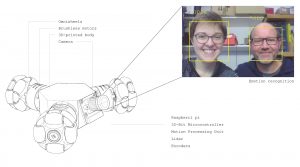

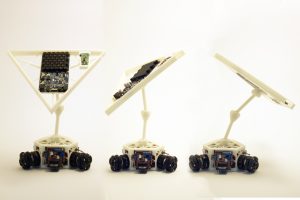

The two story family house where I visit Katrin and Adam was built by Katrin’s great grandfather. He used to run a taylor shop on the ground floor and raise goats in the garden. Now the home is the site of a different sort of cottage industry. Upstairs robots are being assembled. If everything goes according to plan, soon the swarm is going to rise by an order of magnitude, from a first set of 10 prototypes to 100 units. Adam jokes that to meet the deadline he must first transform himself into a production line robot. These creatures cannot reproduce themselves autonomously just yet.

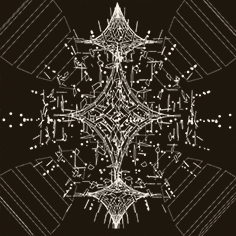

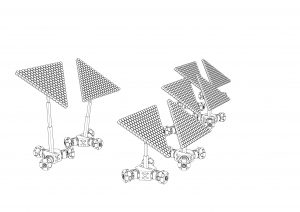

Katrin and Adam met in Switzerland during an exhibition in which Adam was busy with a pair of robotic arms capable of moving particles using acoustic levitation. For the last two decades Adam has been working with sound and robotics, fascinated by things like acoustic lenses and how sound messes with our perceptions. Back in 2001 he had a residency at the Defense Science and Technology Organisation in Adelaide where he first was able to explore the possibilities afforded by hyper directional sound. Katrin matured her interest in robotics during her architecture studies, first in Wuppertal and then at ETH Zurich. Her research approached digital parametric design by devising a swarm of builder drones able to cooperate to construct temporary pavilions. As is the case with most in the architectural profession, her ideas remained designs waiting for realization. The encounter between Katrin an Adam presented the opportunity to join the expertise of both to give life to an actual swarm of artificial entities. Katrin become the coder and Adam the hardware guy.

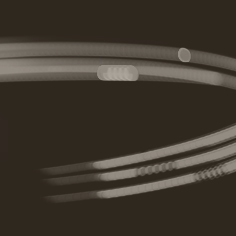

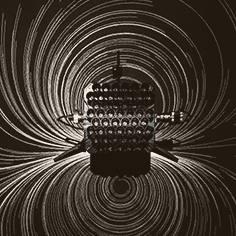

These little hexagonal cars that are dancing around at my feet run a physical implementation of the well known algorithm know as Boids, created by Craig Reynolds in 1986, which simulates the flocking behavior of birds. I remember playing with that code myself in programming class, but then it was just triangles on a computer screen. Now it’s hexagons running free on the floor.

Dumuchel and Damiano in their recent Living with Robots explain how the field of artificial ethology is concerned with creating bio mimetic robots that serve as scientific instruments who’s function is to prove theories about animal behavior. There are advantages in utilizing robotics over computer simulations. Robotics allow to include in a model the interplay of physical forces that are too complex to simulate accurately in virtual environments. Moreover, robots have a presence that compel human responses and enable interaction within the same space that our bodies occupy.

The broader question that Craig Reynolds was responding to with Boids is how swarms of autonomous agents organize themselves without a central authority. Boids was able to model the flocking behavior of birds using 3 principles: separation, alignment and cohesion. The direction taken by each agent at every program cycle is the vector sum of these 3 parameters. Separation indicates the distance that each agent will seek to maintain from its neighbors. The alignment parameter steers agents towards the average direction of nearby flock mates. Cohesion steers agents towards the center of the flock, seeking to maintain the flock as a whole. If we imagine these 3 parameters along the lines of Valentino Braitenberg’s interpretation of robotic motion, we could call them: personal space, conformism and loyalty.

One of the allures of studying swarm intelligence is the promise of developing better systems of governance. Systems in which each individual member of a group is effectively reflected in collective decision making processes. Documentary maker Adam Curtis in All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace refers to an experiment which was carried out during the SIGGRAPH 91 convention in Las Vegas. Thanks to state of the art computer vision, 5000 participants equipped with color coded paddles were able to collectively play the video game Pong. The game was projected on the large screen of the venue. The system tracked in real time the paddles held by the audience, steering the game paddles according to the input provided by the crowd. The experiment demonstrated a new way for collective decision making that promised all but a societal revolution. Fast forwards almost three decades and much of the earlier enthusiasm for digital information technology is gone. Stock market instability, cyber bullying, data mining, online censorship and fake news.

Now it’s time for the difficult question: where is the empathy in this Empathy Swarm?

Empathy has been a buzzword since scientists scanning the brains of monkeys stumbled into the idea of mirror neurons. When we look at someone that is exhibiting pain, we experience pain ourselves. Neuroscience explained what theatre audiences felt for centuries in front of the sorrows of Antigone or Ophelia. Capitalising on this discovery, Jeremy Rifkin in The Empathic Civilisation proposed to harness these newfound brain mechanics to tackle global challenges such as climate change. If we could just feel the pain of fellow humans on the other side of the planet, we might take the steps necessary to reform our consumption patterns.

One of the obstacles that lie in the way of pursuing Rifkin’s proposition might be that, within the online environments that connect us to the world at large, humans have shown to express a serious empathy deficit. In 2009 the Dutch artist Tinkerbell published Dearest Tinkebell, a printed archive of hate mail and death threats she received after claiming to have tailored a handbag using the fur of her own cat. “I seriously hope you become the obsession of a sociopath and that he makes a purse out of you” echoed with variations over the hive mid.

Is it true what they say, that people with social impairments created the internet in their own image?

The recluse inventor assembling robotic companions as compensation for a lack of human connection is somewhat of a cartoonish stereotype. It makes sense that those who are not at ease with the complexities of volatile human emotion would find comfort in alternate realities where the behavior of companions can be modeled parametrically to fit within a predefined comfort zone. Think of the androids in the sci-fi series Westworld, where the hosts of the amusement park can be reprogrammed to be more submissive or aggressive at a flick of an app.

Where fantasy starts to meet reality, the field of social robotics proposes to develop new forms of artificial intelligence able to recognize and respond to human emotion. One of the inspirations for Empathy Swarm is the work of roboticist Angelica Lim. During her PhD at Kyoto University she developed SIRE, a multimodal system allowing AI agents to recognize and exhibit emotional responses. Differently from other researchers in her field, Angelica Lim chose not to go for the more obvious path of reading and imitating human facial expressions. SIRE stands for Speed, Intensity, Regularity and Extent. Analysing the variations of these 4 parameters, SIRE attempts to infer an emotion from bodily movements and vocal dynamics. The system then creates a reference database from which it can generate its own emotional responses. An AI that learns how to become emotional from example.

And here lies the clue of the question. The challenge of teaching robots to develop emotional connections, however unlikely the prospect of creating truly emotional machines may be, might give us some insight into how to teach each other to be more caring.

Searching for emotion where it’s the least expected is at the core of Empathy Swarm. An experiment carried out in 1944 by psychologists Fritz Heider and Marianne Simmel is presented by Katrin and Adam as reference. Heider and Simmel’s experiment consisted in showing a short animated film to a group of test subjects and then asking them to describe what they had seen. Their film shows a few basic geometrical figures in motion. Most spectators easily decode the choreography as a short story in which the figures represent people enacting emotions such as love, anger and sadness. No need to go to all the trouble of drawing cartoons of a mouse, we can connect emotionally to the adventures of a triangle and a circle just fine, so why not empathize with a group of hexagons?

Current research into social robotics finds a direct application in fields such as healthcare, where robots sit in for human caretakers. This relationship appears to be reversed as I observe Katrin and Adam intent on the development of Empathy Swarm. At work in the studio, they are the human caretakers while the robots are their dependents. As I approach the creatures, I get too close an inadvertently interfere with their tracking system. The creatures loose their bearings and run out of their playpen. We have to patiently chase after them and bring them back to safety. If we must raise robots that have empathy, Katrin and Adam are doing it the traditional way, like a loving couple raising children.

My first globe of sourdough looks like it’s ready to put in the oven. Humans and yeasts have been collaborating for a while. There is promise in collaborations between radically different entities.

Funded by the Digital Culture Programme of the German Federal Cultural Foundation.

Funded by the Federal Goverrnment Commisioner for Culture and Media.

The work is developed in the framework of the “Intelligent Museum Residency” at ZKM and Deutsches Museum.

The project is supported by the project stipend for artists during the Corona crisis by North Rhine-Westphalia.